The dad who taught his daughter how to kick a football in the last days of Yugoslavia

My father Petar taught me a lot of things, a truth universally acknowledged by pretty much everyone in our inner circle.

Before he passed away at the excruciatingly young age of 36, dad taught me – amongst other things – how to do the multiplication tables LIKE A BOSS, to always wash my face with cold water in the morn, how to dive (Crikvenica, August 1993, our last family holiday as a foursome and a privileged respite from all-war-all-the-time), how to go down a waterless slide on the Adriatic Coast (fill a plastic bag with water and put it under you), how to fearlessly speed downhill on my bike, how to blitz crossword puzzles (a pastime I haven’t picked up in my adult years, lamentably), how to never be a xenophobe or a raging imbecile who categorises ethnicities (he and mum both taught me this commonsense “love thy neighbour” stuff).

Hell, I even had my inaugural driving experience with dad when, at the ripe old age of five, he put me in his lap in our charming, old orange Fiat Bambino and said, “Wanna take it for a spin, kiddo? Here, go on, drive.” So I gripped the wheel with all the mettle my age afforded me (a helluva lot) and proceeded to, er, “drive”, by which I mean I did relatively well steering until I, of course, ruined the effort by almost veering straight into a ditch before dad swiftly intervened.

Dad also taught me – drum roll, please – how to kick a football properly.

Now, you mightn’t deem that to be such a big deal but, um, hellooooo: totally big deal. Huge, even. I mean, you don’t grow up in football-obsessed Yugoslavia (even, at that point in time, with Yugoslavia on the rocks) and not know how to kick a football (blasphemy!), especially if you’re a kid where the possibility of spontaneously kicking a soccer ball around your apartment building is always looming. To not know how to kick a football would be worthy of major side-eye…maybe even stink-eye. Never mind that girls “weren’t expected” – ahem – to be good at soccer or even play it recreationally. (Pfft, spare me!)

Dad teaching me to kick a football in our hometown of Karlovac, Croatia, is one of those halcyon nostalgia-tinged memories firmly ingrained in my memory bank, on lockdown in an impenetrable safe. (For some reason I just thought of a crackly Super 8 film reel…or The Wonder Years opening credits, ahh.) The kick tutelage happened on a summery day in either 1990 or 1991, before war became our quotidian, like some gnawing vulture and before my brother and I faced a regular barrage of verbal abuse from a few neighbours who loathed our Serbian ethnicity. (The tragicomic question of the time across Yugoslavia from a lot of kids to parents was “So, what am I?”)

We were playing around and the ball came to me. I kicked it to dad or my brother Dejan; I forget now. The next thing I knew, dad chortled and stopped the ball, walking over to me with a smile while Dejan smirked like only a brother can. “No, no, cutie…you don’t kick with the tips of your toes. Look, like this,” dad indicated, grazing the inside of his foot against the ball, “this is the part you want to kick with. That’s the proper way to kick in football.”

I tried this new correct method and got the hang of it, resisting the instinctive urge to kick with my toes because, to me, kicking with toes was easier and made my kick stronger. Inside of foot, inside of foot. “That’s it – bravo!” If anything, I refused to give Dejan the satisfaction of my amateurish toe-kicking, which he’d no doubt point out and ridicule, because sibling rivalry.

It’s a total understatement that, given I was the quintessential daddy’s little girl, I loved watching dad play football; he looked content, childlike. Light-footed, skilled and natural, and always having fun with it. To my “in awe of dad” self, he didn’t look any less capable than the professional players du jour. (Ha!) I mean, it wasn’t enough that he was bright and brilliant, and had old school movie star looks for good measure, he was great at football too. (Seriously, dad was a total Elvis. Er, Elvis in his prime, not late-70s-jumpsuit-ripping Elvis.)

In our family, we were traditionally Crvena Zvezda supporters (Red Star Belgrade). It was a hallowed tradition, passed on from generation to generation; you did not stray from the sacred fold, see. Defection: sacrilegious.

Dad routinely watched Red Star and other teams’ games and we sat alongside him. Mum (decidedly not a football fan) would sit with us in the lounge room and barely feign interest in the matches while busying her hands with other more interesting things and smiling. That scene right there is like the epitome of the idyllic family moment…fortunately we had many. Dad would shout and cheer, jeer and scoff, let out delighted whoops, jump out of his seat at dodgy ref calls and flail his arms towards the TV and routinely yell out colourful profanities. For us, that was entertainment unto itself. The way dad followed the match, well, it seemed so grown up and cool, and we regularly got a glimpse into that world, so serious and exclusive, seemingly a whole lifetime away.

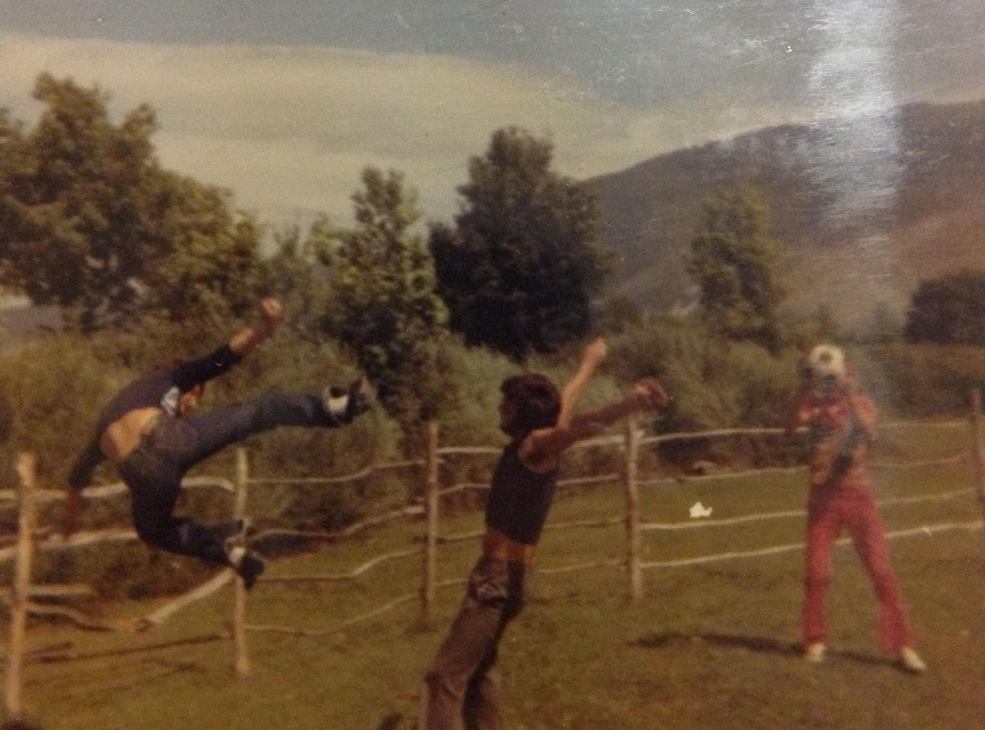

Dejan and I periodically perused the family albums in our Karlovac apartment. Towards the back of one of the albums, there was a sequence of photos of dad and his friends playing football in their village of Kijani, culminating with dad leaping off the wooden fence with a cross-between a scissor kick and something vaguely karate-esque.

We’d laugh and swoon, gleefully asking dad for the umpteenth time to explain exactly how he managed this supreme masterly stroke of all-time footballing greatness, and dad would laugh and recount afresh the tale we knew in detail, but whatever, we wanted him to tell it again. And again and again. It never got old. “Wait, weren’t you scared you’d plummet to a certain death and break your neck and/or many bones?”

My paternal uncle Dragan tells me that dad played for the primary school football team starting in grade 5, as well as playing for the grammar school (gimnazija) team in his adolescence. As my uncle so lovingly puts it, in life dad did everything brilliantly, football included, and apparently he was one of the better players on the gimnazija soccer team. Dragan also said that, in the years after high school had ended, dad and a friend once organised a major, unforgettable soccer match on a stretch of grassland below the village houses, going so far as to make the goals themselves, which included dragging wood over from a nearby place. Now that’s commitment!

The whole Kijani village was present and it was a match with all the frills: lamb on the spit and mostly soccer-themed music blasting from the speakers. The speakers were connected to one Vlado Sedlan’s house as his was the closest and required the least amount of cable. (Ha!) People both young and old turned out in force to watch two opposing forces battle it out: bachelors versus husbands.

Ah, to have witnessed this enthusiastic spectacle!

Another one of the old family photos sees dad in a pre-match team photo at the Day of Railway Workers Cup with his Karlovac colleagues. I couldn’t tell you which year but my guess, based on the photo, would be…late ’70s? But that’s not important, what’s important is that, lo and behold, they had matching Puma uniforms for this all-important Cup. Snazzy. (As you’ve probably figured out by now, dad is that striking fellow holding the ball.)

Vaguely related to this photo is the separate Workers’ Sport Tournament (played Yugoslavia wide) at which my dad participated with his Karlovac Railway Station colleagues, as uncle Dragan mentioned via email. Funny story: dad asked Dragan to play for their team since my uncle was also a good player, and when they were registering with the delegates, dad proceeded to smuggle his little brother in under the auspices of being a railway station employee. Dad 1, Delegates 0. They reached the final then lost – Dragan says dad had a lot of misses during the match and that they should’ve easily won the final but: “That’s football, it happens.”

* * *

Dad was only 36 when, on 13th Sept 1993, he was wounded from errant shrapnel during one of the worst major shelling campaigns in our hometown (shelling continued until war’s end but never to that extent). It felt like the earth would give way and crack open from the whizzing grenades; the bombing was omnipresent, terrifying, apocalyptic. Sickeningly loud; earth-shatteringly so. Dad was holding down the fort at work and found himself in a wrong-place-wrong-time situation. The shrapnel went into his brain. The tiny remnant of a grenade was subsequently removed days later during surgery but, after some time, the residual bacteria in his brain caused meningitis. Dad fell into a coma and died 1st November 1993. Suffice to say, our world fell apart; we were inconsolable. Hollowing, crippling sorrow submerged us. I was a few months shy of turning nine, already mature beyond my years after two years of war, when my world, for me, completely tilted on its axis. And then, nine months after dad’s death, we emigrated to Melbourne, Australia, thanks to the heroism of my magnificent, lionhearted mum, Ljubica.

Sometimes, against my better judgment, I read comments about the catastrophic Syrian refugee crisis, one of the worst humanitarian crises of our time after more than five years of brutal civil war. I pore over the hateful, jingoistic and ignorant groupthink, laugh in disbelief at the way they demonise refugees and try to make them the bogeyman, and I think, “You fucking idiots, you really have no idea, do you?”

After dad’s funeral, several hours into the wake, Dejan and I escaped outside for some fresh air and in part to avoid the pitying looks of guests. The November air cooled our faces, eyes painfully swollen from endless tears, cheeks red and puffy from the sobs that wracked our bodies. Footballs were being kicked around, hopscotch and elastics played. We were completely paralysed by anguish and just stood on the sidelines, observing, not speaking. I glanced at the pitch that would never again see dad’s steps.

It wasn’t long before those same neighbours that had developed a penchant for tormenting us approached and I stiffened, half-expecting them to express their condolences, like pretty much all of the kids had. But no. “We’re not sorry your dad is dead because you’re Serbs.” Cue gasps and more crying. Dejan mumbled an outraged expletive at the siblings, grabbed my hand and we ran back up to our apartment.

In the interminable weeks and months following dad’s death, I would wake up and gingerly open the door to the lounge room, half expecting – hoping, praying – that everything had just been a horrific nightmare or a huge misunderstanding, you see, and that I would be rewarded with the image I hungered and ached for so desperately: dad lying down on the couch, or sitting there with the paper and his morning coffee, the scent of which usually wafted over to my room. Maybe he’d be watching football highlights. It was possible, I wagered. I mean, hey, miracles happened. Wasn’t that what all those stupid TV shows I inhaled had taught me?

My eyes still stained with slumber, I would take a deep breath and waddle into the living room, heart in throat. Alas, reality hit every time and hit me with the force of a hundred – nay, thousand – locomotives. Only the ghosts of his former self remained. I could vividly conjure up the fatherly outlines and shadows, a hologram of one Petar Kesic watching his beloved football matches. That was all I had left.

I would’ve given anything in those moments – begged, stolen, crawled on hands and knees through punishing terrain – to see dad watching his Red Star matches with utter concentration, to see all that I had seen through the years and had taken for granted, but gosh it hadn’t been enough. It wasn’t nearly enough.

And it still isn’t, much as I cherish all the gorgeous, priceless memories I have and cling to for dear life, as though I’m fearful that anything other than subconscious clinging will result in my being struck down with some convenient form of PTSD-like amnesia. Dad was a forever thing, invincible; dad not reaching old age was not an option. Until it was and that option was forced on us, engulfing us. I mean, it was dad, dad. How could someone so alive perish? Everybody knows fathers are all-powerful, all-knowing, everything.

War had cruelly and tragically snatched my father away from us and…there was absolutely nothing I could do about it. But those times when my despair and anger boiled over and became overwhelming, suffocating, I imagined exacting my revenge on War.

Getting vengeance on something intangible at almost nine years of age perfectly illustrates the damage war does to children and adults alike, and how effectively it fucks them up, at least initially while it’s all still raw. I’m happy to report that, while the trauma never goes away, time makes it so that you very rarely feel it or think of the bad times, becoming more inclined to think of the good times the vast majority of the time. But, then, as a child I had the luxury of a grieving process.

I wished for War to become tangible, manifest itself as a hideous, evil, flesh-and-blood person with a demonic-looking head (a Hydra or a Minotaur, if you will), so I could wring its neck(s) with my bare hands, and do so with gusto, do it for my family and all those like us whose loved-ones had been civilian war victims all over the Former Yugoslav territory. I wanted to lunge at this mythological creature and tear at it violently, have at it, snuff it out, destroy it like it had utterly destroyed us. Maybe even arrange a duelling cowboys face-off à la pistols at dawn (testament to how many spaghetti westerns I watched as a kid) wherein I’d know, without a shadow of a doubt, that I would emerge victorious and avenge my father’s death, smugly blowing the puff off of my smoking gun. Maybe I’d even lob a soccer ball at War’s crumpled heap, as a final parting gift to the scumbag.

No toes, inside of foot.

Take that, War!

I’d half-heartedly play during ceasefires and watch kids playing football out on the pitch, soaking up the grenade-less time to get in as much soccer time as humanly possible. It’s funny, however much I adored and yearned for ceasefires, I always found them insanely tense because, well, it just meant more shelling was around the corner so, you know…you could never fully relax wondering when the next round would start. And don’t even get me started on the bloodcurdling wail of the emergency town siren that would start up before every shelling. I’d watch the kids play with boundless energy and laugh like we weren’t in a totally insane situation. What can I say, kids are resilient in wartime.

* * *

There’s a lot of dad in me when I watch football and I never really realised it until a few years ago. For one, I get pretty fired up watching games – not unlike how he used to. My aunt Anka, dad’s sister, laughed and laughed as we watched a World Cup qualifier once circa 2013. I caught her laughing at my worked-up self but attempting to stifle said chuckling. I’m my father’s daughter in many ways, and loving football is no exception.

I spent a good chunk of the 2014 World Cup cheerfully thinking of dad and pondering things like, “Ooh, I wonder what dad would say about that assist or Cahill and van Persie’s sublime goals,” or, at the breathless end of the blockbuster Germany v Brazil semi, for which I got up at the crack of dawn, “Holy cow, dad would’ve absolutely loved this 7-1 thrashing!”

Every time my husband Igor and I kick a soccer ball around in a park, I still, to this day, concentrate extra hard in the seconds before I intercept the ball, making sure I kick the ball exactly right, with the inside of my foot; not the tip, never the tip.

Just like my father taught me that summer day back in the early ’90s; a sliver of his profound, indescribable legacy. Get the kick right, Nev, do him proud.

And, damn, I know he’d be beyond delighted at the association; that he’d be proud as punch that I inherited his love for football; that he’d want to be right here along for the ride.

That he’d laugh and laugh knowing I still avoid, at all costs, kicking that ball with my toes.

“Not all of me is dust.

Within my song,

safe from the worm,

my spirit will survive…”

(Pushkin)

What a story. Of you, your dad, and you and your dad. Great read. Thanks for sharing, Nevena.

Thank you so much, Adam!

An absolutely beautiful read! Thank you for sharing your story.

Heartfelt thanks, Kate!