There were plenty of pop stars around in the early 1970s to keep a teenage girl entertained: dreamy Partridge Family beau David Cassidy, the clean-cut Mormon charms of Donny Osmond and even spunky Daryl Braithwaite of Australia’s very own Sherbet, to name just a few.

But Denise McFarlane wasn’t interested in pop stars. At least not after she experienced her first live rock band. No, McFarlane and her mates hit the harder stuff from an early age.

“It wasn’t so much on the radio because I think the only song I heard on the radio was ‘Love You Babe’. For me, my main memories were that my sister’s boyfriend was a sharpie and I happened to be a sharpie as well and that’s what we did — we just listened to Lobby,” McFarlane tells Shoot Farken.

Between 1972 and 1975, Melbourne’s much-feared sharpie tribe had found their soundtrack: the Coloured Balls, featuring Australian guitar legend Lobby Loyde. The band’s heavy rock struck a chord with the disaffected kids of sharpie suburbia — just like the sharpies, the Coloured Balls were…ballsy.

Similar to the relationship between mods and The Who in the UK, the short-haired, rat-tailed, ‘connie’ cardigan-wearing sharpies and the Coloured Balls developed an intense, sometimes conflicted bond which came to define both groups.

“Their style of music: as a 13-year-old all of a sudden it was just there. That’s who we followed and they looked like us because they shaved their hair off and had the tails and we all had shaved hair and tails — yes, even me. Hard to imagine now, but I did,” she says.

“It was loud and it was fun. You could just lose yourself in it.”

Growing up in the outer eastern suburb of Ferntree Gully in Melbourne, Australia — just another teenager hanging on for dear life at the arse end of the world — Denise had found her tribe. She belonged and her mates all felt like they belonged; they were part of something that mattered.

According to sharpie folklore, the tribe had evolved from the “sharps” of the 1950s and ’60s, and as the name implies, these were teenagers and young adults who took what they wore seriously. Fashion and music had always played a big part in the sharpie story, as did some of the gang violence newspapers at the time reported in breathless, tabloid tones of condemnation.

“Knives, knuckle-dusters and ice-picks are part of a really ‘sharp’ teenager’s dress,” The Argus newspaper reported in 1955.

As the demographic tidal wave of post-war babies grew up to become bored teens in dead-end suburbs, youth tribes gained in number and those numbers meant strength on the streets and in the clubs.

In Melbourne especially, the sharpie movement took hold in the new estates of the suburban sprawl, with working-class people moving out of the inner city slum suburbs into the quarter-acre blocks that represented the Great Australian Dream in the new age of Cold War peace and Long Boom prosperity.

There was no doubt that by the ’70s, sharpies had a reputation — and it wasn’t always good.

“They all walked across the road when they saw you coming,” McFarlane says now laughing, four decades or so later.

“But in saying that, within our groups we had long hairs, if they were your friends from school or something, they were part of it. It’s just that some chose to take the hair off and others didn’t.

“My mum used to cut my hair and one day I remember she said, ‘I don’t want to cut your hair anymore because I’m sick of people looking at you horrible!’”

Denise McFarlane (sitting front) and friends at Melbourne’s Moomba festival in 1974 or 1975

From Thomastown in the north to Frankston in the south, from St Albans in the west to Croydon in the east, sharpies roamed the streets and trains of Melbourne. Gang fights were common.

“For me, I don’t know if I was completely naïve or if we were just before all of that because my time as a sharpie, in the mid-70s, it was just about going along and having fun and dancing and seeing good music,” McFarlane says. ”I don’t think I saw that aspect of it, certainly heard of it, the boys would go out fighting on a Friday night but that wasn’t show night, the next night was show night.”

She started going to gigs with her older sisters when she was 13, including the sharpie jamboree known as Summer Jam held at the Melbourne Showgrounds: “I was the youngest sister, the tag-along.” To this day, she’s still upset she never made it to the band’s famed show at the Sunbury Festival in 1973.

A bona fide Melbourne rock chick, 40 years later she still loves seeing bands. She likes all sorts of music, but her face lights up when she talks about the classic ’70s Aussie rock bands like the Coloured Balls, Buffalo or Buster Brown she saw as a teenager in the town halls, high schools and sports clubs of Melbourne’s burgeoning live music circuit.

One such show was seeing a raw and hungry AC/DC at a local ice-skating rink.

“AC/DC was always a big favourite because we had Iceland, which was the Ringwood ice rink, so the bands always used to play there. Being a skater, I got the opportunity to skate with Bon Scott.”

McFarlane laughs when asked whether the AC/DC singer was a good skater.

“No. He was off his head! And being a kid, a teenager who looked like a tomboy, I think he was just really thankful to have somebody that could skate with him who wasn’t trying to hit on him,” she says.

“We were pretty spoilt. We usually had Lobby Loyde, we had Buster Brown, we had Buffalo, Madder Lake, Thorpie [Billy Thorpe and the Aztecs], and Matt Taylor, who was completely different again.

“We just loved Australian live music that gave an honest show and Lobby always gave an honest show.

“Lobby was ours. And I think because he did cut his hair, as silly as it sounds…it was really so distinct back then, so the Coloured Balls, that was our band.”

Melbourne Sharpies, by Greg Macainsh

Heavy Metal Kids

The Coloured Balls released two official studio albums in their short existence, Ball Power (1973) and Heavy Metal Kid (1974). The band was also featured on the Summer Jam live album, playing with another legendary figure of Australian rock music, Billy Thorpe. The Summer Jam album, recorded live at Sunbury ’73, features one of the signature Coloured Balls tunes, “G.O.D (Guitar Over Drive)”, an epic track that well and truly lives up to its name.

Even though the band was relatively short-lived, they’re still revered by rock aficionados, including Pavement’s Stephen Malkmus, who covered the Coloured Balls classic “That’s What Mama Said”.

New York rockers Endless Boogie are also big fans, with guitarist Paul Major calling Ball Power “one of the most rocking albums ever made”. He was surprised when he toured Australia that the band wasn’t better known.

Major told Mess+Noise: “That gave me something to think about, that people from Australia weren’t necessarily aware of Lobby’s music. A few times here I’ve had people come up to me and thank me for turning them on to the Coloured Balls. In New York I might expect that but I was really surprised it happens in Australia too. They should be as big as AC/DC, you know?”

Rolling Stone magazine senior editor David Fricke called Lobby Loyde “the founding architect and guardian spirit of Aussie garage rock and heavy music for more than three decades”.

“Loyde disciples AC/DC took Aussie power boogie to the world in the Seventies — but only after Loyde set the high bar at home with the bludgeoning majesty of Coloured Balls, on 1973’s Ball Power and 1974’s Heavy Metal Kid.”

Kurt Cobain was also known to have been a fan, as is Henry Rollins.

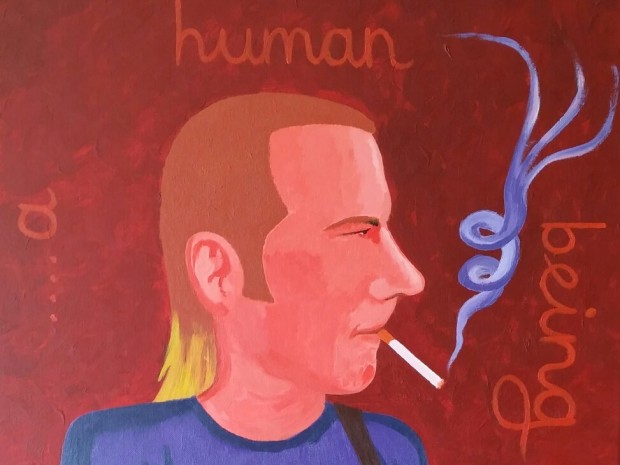

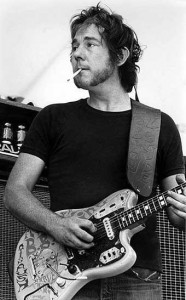

Guitar slinger: Lobby Loyde with his customary cigarette

It’s fitting the band’s two official studio albums (a third LP called The First Supper Last: Or Scenes We Didn’t Get to See was recorded in 1972, but not released until 1976) have been reissued recently on vinyl by Australian label Desperate Records. The Coloured Balls are one of those bands that should be heard on vinyl. While the Aztec Music label’s CD reissues from about eight years ago were fantastic, there’s something very right about this seminal slice of Oz rock history finally being on record again.

Desperate Records label boss Dave Lang grew up listening to punk and underground rock and it was through these bands that he first heard about Lobby Loyde and the Coloured Balls. Geelong band Bored! covered the Coloured Balls song ‘Human Being’ on their debut EP in 1988, which is what piqued Lang’s interest in all things Lobby Loyde.

“This was also a time when a lot of people who had grown up on punk were investigating pre-punk hard rock and really digging the sounds of everything from Black Sabbath to Blue Cheer, AC/DC and Deep Purple, early Rose Tattoo and the Aztecs. Bands like Black Flag, Hard-Ons, etc, who flaunted and talked of their influences…really opened up the idea of people interested in punk and nominally ‘indie’ music to acknowledge the raw brilliance of this music.”

Lang’s interest in the Coloured Balls was reignited by Aztec’s CD reissues. Through this connection, he started working with Gil Matthews, the head of Aztec, to put the Coloured Balls back on vinyl. Matthews had intended to do a vinyl reissue a few years ago but the project had been put on hold indefinitely.

As the producer of Heavy Metal Kid and someone who knew the band’s sound intimately, Matthews was uniquely qualified to oversee the vinyl remastering of the albums in the absence of Loyde, who had died in 2007 from lung cancer.

Lang says Matthews did an excellent job on the remastering: “It’s definitely the best sounding version ever available.”

Ball Power is a grunting, snarling record full of adrenaline-charged rockers. Its influence is obvious in the sound of Australian rock bands like X (whose albums Loyde produced) and the Cosmic Psychos.

Heavy Metal Kid, meanwhile, showcases some of the more adventurous and idiosyncratic aspects of Loyde’s musical oeuvre, harking back to his work in the ’60s.

“Ball Power is basically non-stop, high-energy, loud and distorted rock ‘n’ roll. Heavy Metal Kid has a piano ballad, for Christ sake! But it works,” Lang says.

“For me, what makes Heavy Metal Kid such a great album is its peak and valleys…I actually think that HMK is easily the equal of its more famous companion album, Ball Power, and its eclecticism is a beautiful thing. Both albums were of and out of their time, if that makes any sense.”

Matthews remembers the hours spent in the studio with Loyde trying to finesse the sounds and songs on HMK.

“Ball Power wasn’t really produced; Ball Power was just recorded. They got in the studio and went bang, bang, bang and recorded it. HMK is actually produced. We sat around thinking what sort of sounds we wanted, ” he says.

Sometimes the sounds came from unlikely sources.

“The track called ‘Metal Feathers’, that’s got a Mellotron on it and there’s a bell on the end of it. I can tell you now that is the water meter cover from the South Melbourne police station because we didn’t have a bell when we were trying to record the fucking thing! So I went down to the police station and asked them if I could borrow the metal cover off their water meter, and that’s what it is.”

Lang says the two albums stand as examples of an era when Australian music was finding its identity.

“Certainly there were a ton of great Aussie bands in the ’60s, but the 1970s, which was also guilty of coughing up a lot of terrible Australian bands, was when it really came into its own.”

VIDEO: Coloured Balls, ‘Heavy Metal Kids’ from Heavy Metal Kid

Rock ‘n’ Roll Tribes

Matthews had been playing drums in bands on Melbourne’s buzzing cabaret circuit in the 1960s, backing musical theatre types and pop singers. He had grown up as something of a drumming prodigy, touring the US with jazz greats Gene Krupa and Buddy Rich as a child.

He says the popularity of live music in Melbourne during the ’60s meant there was plenty of work for good musicians and plenty of bands for punters to see, including Loyde’s pre-Coloured Balls groups the Purple Hearts and the Wild Cherries. In fact, Matthews had already worked with Loyde, engineering the Wild Cherries single “I am the Sea”.

“The scene was extremely different to what it is now. You had venues everywhere, basically on every street corner. The bands were all playing three or four gigs a week. There were lots of gigs in this town [Melbourne], say at Sebastian’s, Bertie’s, the Thumpin’ Tum, and they weren’t licensed, people actually went to see bands,” Matthews says.

He crossed over into the big, bad world of rock ‘n’ roll when he heard talk around town that Billy Thorpe & the Aztecs were looking for a new drummer. Thorpe had been one of the country’s biggest pop stars in the mid-60s, but had taken his music in a heavier direction in the late ’60s.

“I got mixed up in that crowd in March of ’71 when I joined the Aztecs, so really I met all these people in early ’71 and became part of the clan,” Matthews recalls.

Going from the buttoned-down cabaret circuit to the excesses of Melbourne’s heavy-drinking rock scene was a wild ride for Matthews, but not something he would ever regret.

“If I had my life over again I would do exactly the same because what I did was what everyone dreams about doing: playing in a fucking rock ‘n’ roll band and partying for 20 years!”

Billy Thorpe & the Aztecs had undergone a radical transformation, much of it due to Loyde’s influence after he joined the band in late 1968. The band’s louder, heavier and more progressive new sound alienated a lot of Thorpe’s older fans, who came along expecting the middle-of-the-road fare Thorpe had churned out in his pop star days.

Matthews says Loyde “basically taught Billy how to play guitar”.

“By the time I joined the Aztecs in early ’71 Lobby had already been in the Aztecs and left. But Billy and Lobby and all the Aztecs were still living in in the same house together.”

A house which no doubt saw its share of partying.

Upon leaving the Aztecs in ’71, Loyde recorded his highly regarded prog-psych album Plays George Guitar. However, it wasn’t long until he was back in the fray with a new band, the Coloured Balls, formed in early 1972 with Janis ‘John’ Miglans on bass, Andrew Fordham on guitar/vocals and Trevor Young on drums.

“The two bands [Billy Thorpe & the Aztecs and the Coloured Balls] were really intermingled; they were like ‘brother’ bands,” says Matthews, who played drums on the first Coloured Balls single, ‘Liberate Rock’. The bands soon started playing around town together, shaking the foundations of many a Melbourne venue with their high-decibel rock. Matthews remembers a lot of the shows being wild affairs.

“Lobby was a pretty quiet sort of guy, really. We [the Aztecs] were probably a bit more rebellious. He didn’t cause any woes for anyone, whereas Billy would go nuts. Billy would jump off stage and just whack someone if he wasn’t happy. It was a different thing altogether for the Aztecs than it was for Lobby.”

“The Aztecs had a whole group of people follow us everywhere, and this is back in the sharpies and widgies era. The sharpies were a Lobby thing, a Coloured Balls thing, they weren’t an Aztecs thing. Lobby had the skinheads sort of chasing him all over the place, going to all his gigs. We had more of a boozy, smoking dope, hippy sort of rock ‘n’ roll, bluesy crowd.”

The violence at Melbourne rock shows wasn’t just coming from Billy Thorpe jumping into crowds and smacking some respect into snot-nosed punters. Members of the audience were getting stuck in too, as Melbourne rock identity Bruce Milne recalled in an article about sharpie culture for Perfect Sound Forever.

Milne said a lot of the violence at shows was generally “overstated” by press reports keen to play up the angle of ‘sharpie gang violence’. However, going to a show in Melbourne back then certainly had an edge to it:

The worst Sharpie brawl I saw was at a park in Richmond. It was late ’72 also and there was a concert celebrating the end of the draft and our involvement in Vietnam. Lobby Loyde & The Coloured Balls were playing. Sharpie gangs came from all over. Though there were other bands on the bill, it was definitely the Coloured Balls that everyone had come to see. The band only made it through a few songs before an all-in brawl between rival Sharpie gangs broke out in front of the stage. Lobby jumped into the crowd to sort it all out and disappeared for a few minutes. When he climbed back on stage, he had blood streaming down his face. He grabbed the mic and said, “Fuck this shit, the gig’s over.” And it was. The fighting continued but I’d made another hasty exit.

The sharpies had a distinctive look that overlapped with elements of British skinhead culture, but they were ultimately a very Australian phenomenon. The confronting, almost punk look, combined with a fair degree of youthful Aussie machismo, put the sharpies in line for unwanted attention from other groups – bikies, hippies, surfers, cops, you name it – and shows, especially big outdoor festivals, would sometimes become battlegrounds with readymade soundtracks.

As ‘Sooty’ recalls on the Melbourne Sharps history page:

1973 Sunbury Rock Concert nearly erupted into a huge brawl between the Hells Angels and the City Sharps because of a few young kids from the suburbs, drunk, hitting a bikie over the head with a whiskey bottle and yelling ‘Don’t fuck with the Melbourne Sharpies’. Never forget the next 24 hours, but thankfully the dust settled.

The Aztecs with Lobby Loyde — Rehearsal + Interview

Show Night

Friday night in the McFarlane home was usually spent watching TV.

“We’d all watch The Aunty Jack Show and stuff, and I remember a few times my older aunts and uncles would arrive and there’d be this house full of sharpies, and they’d be all sort of going ‘mmm, what’s going on here?’ But they were always respectful at mum and dad’s so it was never really an issue,” McFarlane recalls.

Saturday night was for going out and seeing a show, often at places like the Box Hill Town Hall. Getting ready for a night out was almost ceremonial for the McFarlane girls and their Ferntree Gully sharpie crew, affectionately known as the “Gully Guzzlers”.

“You’ve got to get in the mood with the music. We’d put Lobby on and crank it up. Then you’ve got to make sure you get your outfit spot on, clean and ironed, because we were pretty sharp dressers. It wasn’t like it was just thrown together, it was pretty well planned. Then you’d get your dreadful make-up we’d all wear. I’d have to plait my hair so I had tails that night.

“It just seemed like forever to do nothing. It was the ritual.”

An important part of the ritual was cranking up the Coloured Balls: “You’d have it on the record player the whole day and you’d wait for the mistake in ‘That’s What Mama Said’ [listen for the premature vocal at 36:21] and all laugh, that was like the moment you’d all go ‘Yeah!’ because it made it real and you’d just listen to that all day.”

Tea would be at home because eating out was too expensive. Then it was time to get a lift down to Ferntree Gully train station.

“My dad would drive us all to the station in his old EH Holden station wagon, I think it was, and we’d be picking up people all along the way so we’d be all packed in their illegally; we’d all be in platform shoes and boots, it was fun. My dad loved it — loved it.”

The local police would often be waiting at the train station, taking names and making themselves known to the kids.

“Then you’d catch the train and wherever you were going, whether it was to the city, or to let’s say Box Hill, at every stop more [sharpies] would get on and you’d all know where to get on. It was like the meeting of the clans, like the scene from Brigadoon when they’re all coming in for the Scottish wedding. Like all the clans would just come together.”

While McFarlane and the gathering horde of sharpie crews gradually populated each carriage of the city-bound train, non-sharpies would often have to watch their p’s and q’s or risk a knuckle sandwich, as Melbourne musician Peter Luscombe recounted to Bruce Milne:

The doors of the red-rattler train opened after it pulled into the station. Standing just inside was a group of Sharpies, dressed up to the nines in their best stomping gear — conny jackets, tight jeans and big platform boots. The leader of the gang stepped towards the door as a young kid was about to enter. “This train’s going straight to hospital!” he said through missing teeth with a shit-eating grin. The young kid jumped back on the platform and waited for the next train.

The shows usually had a few bands on the bill, so the Coloured Balls would play with the likes of Billy Thorpe & the Aztecs as well as lighter weight acts such as glam rockers Hush or excellent blues bands like Sid Rumpo. For music-mad McFarlane, it was like being in a hard rock candy store.

“You’d go into the show and everybody had their little spots around the hall and the one advantage of Box Hill Town Hall was you had the top and bottom sections so when the top show was on the bottom wasn’t, so you always had a band to see.”

Playing on a bill with the Coloured Balls could be a daunting prospect for other bands, both because the Coloured Balls were an impressive live unit and because bands that didn’t cut it were soon told so in no uncertain terms. Punters had come to expect a lot from their bands.

If the Coloured Balls did have a weakness, according to Matthews, it was vocals. Bands like Buster Brown had the combustible street poet Angry Anderson, while rising stars AC/DC had the devilish and charismatic Bon Scott. With the Coloured Balls, the front man duties took a backseat to the music.

“The problem with the Coloured Balls was there really wasn’t a lead singer as such. Billy [Thorpe] was an incredible singer, an incredible front man who could just grab an audience by the neck and control them … Whereas Lobby wasn’t much of a singer, he’d get up there, close his eyes and play guitar,” Matthews says.

But that didn’t bother McFarlane too much.

“The Coloured Balls were solid. If you could walk out of a show and not be sweating and not be absolutely exhausted and your ears weren’t ringing, you hadn’t enjoyed it. He [Lobby] always did that, he always caught the energy of the place,” she says.

The end of the show always rolled around too quickly. The kids would spill out on to the street, phone numbers would be exchanged, meetings arranged, last-minute pick-up lines tried on, and then the train ride home.

“You’d be out by midnight and then you ran — my God you ran — for the last train. We seemed to be always running in those days. And then the police would be waiting for you at Ferntree Gully station. But they weren’t rude or anything, they’d just do it to get their numbers up.”

VIDEO: Coloured Balls live in the ABC studios on GTK playing ‘Devil’s Disciple’

“Lobby’s Lobby, G-O-D, that’s it…”

Speaking in 2006 at Loyde’s induction to the ARIA Hall of Fame, Rose Tattoo singer Angry Anderson succinctly summed up Loyde’s legacy.

“More than anyone else, Lobby helped create the Australian guitar sound,” the former Buster Brown singer said.

“Long before Angus [Young of AC/DC], Billy Thorpe, the Angels or Rose Tattoo, Lobby inspired Australian bands to step forward and play as loud and aggressively as they could. People are still trying to copy it today.”

Loyde never fixed his course long enough to really gain the sort of mainstream fame and attention the bands Anderson mentioned did. His artistic wanderings included writing a sci-fi novel (Beyond Morgia: The Labyrinths of Klimster) not long after disbanding the Coloured Balls and recording a suitably spacey soundtrack to go with it — probably not something that would ever have been part of the game plan for the AC/DC global empire of rock.

For Desperate Records boss Lang, the Coloured Balls fall into the category of rock band that was always too “purist” to ever attain sustained pop success.

“I would simply put it down to the fact that a lot of, possibly most, real and purist rock music — don’t get me started — is simply too ‘real’ for a mass market. There’s pop and then there’s rock. Pop is simply ‘pop’ by the fact that it’s popular; most great ‘rock’ isn’t,” he says.

“AC/DC were lucky and somehow managed to find a huge mass market in the US and Europe by the late ’70s without really compromising their sound at all — the basic riffs and cheeky schoolboy lyrics just hit a note where others didn’t — but they’re an exception.”

“Some music is simply meant for a cult audience and that’s the way it’ll always be.”

Loyde’s music career went beyond the Coloured Balls, encompassing his work in the ’60s right through to his time as an in-demand producer in the ’80s, when he recorded bands as diverse as power pop group The Sunnyboys, synth-dance act The Machinations, and thrash punks Depression. But it’s fair to say his tenure with the Coloured Balls inspired the most fervent passion and loyalty among fans.

Forty years has barely dimmed that flame for McFarlane and sometimes a bit of sharpie attitude still comes through when she has to take a stand for her musical passions.

“It’s funny because I went to a party recently and somebody put Lobby on and we were all dancing and some wives — wives — one of them went ‘Get that crap off’ and we all went ‘Excuse me, that is blasphemy, them there are fighting words, girl’. And then she went ‘OK, now we won’t then’ and I said ‘No, we won’t’.”

Those wild guitar sounds that first made her fall in love with rock music as a teenage sharpie girl growing up in suburban Melbourne have stayed with her ever since.

“Lobby’s Lobby, G-O-D, that’s it, and nothing will ever change that. I might even go out to a Lobby song, don’t know yet.”

VIDEO: Coloured Balls, ‘G.O.D’ live Sunbury ’73

The Coloured Balls vinyl reissues are available on Desperate Records through Aztec.

Feature image painting of Lobby Loyde by Brown Hornet.

Further reading on sharpies:

- Check out R.K. Payter’s sharpie novel, Heavy Metal Kids, via Lulu.

- Julie Mac, Rage: A Sharpie’s Journal, Melbourne 1974-1980 and Snap: Sharpie Urban Folklore 1952-1987

- Melbourne Sharps

- Skins ‘n’ Sharps