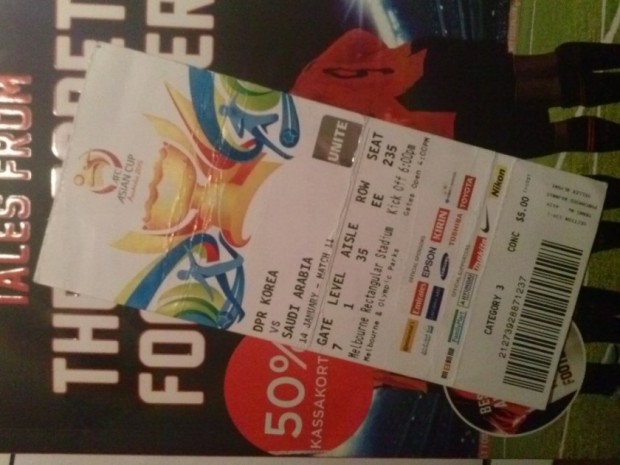

I am reading James Montague’s book, Thirty-One Nil: On the Road with Football’s Outsiders: A World Cup Odyssey. My book mark – my DPR Korea vs Saudi Arabia ticket – had fallen out and in a rush to clean up miscellanea off the floor, I accidentally put it in the bin.

Realising my mistake the following morning, I looked for it; and indeed it was in the bin. I removed the book mark and it was relatively unbesmirched; just a few more creases.

Montague’s book includes photographs of children brandishing their FIFA World Cup (qualifying) tickets to such relatively uncovered games as Palestine vs Afghanistan and the US vs Antigua & Barbuda.

Of the three games I went to at the Asian Cup in Melbourne, this was the only game for which I had a real, actual, one-off, coloured ticket. The others, which I had bought online, were delivered to my email account: if I lost them, I could print another.

But the ticket reminds me that my friend Josh and I only paid $5 each for our tickets. We had arrived relatively late to the game and were queuing at the back of a line when we were offered tickets. Josh paid the couple quickly with a $10 note, and it was only as we were about to enter the stadium did we realise that they were $5 concession tickets. We strode boldly through the turnstiles: no problem; such a thing wouldn’t happen on Melbourne’s public transport with its notoriously heavy-handed ticket inspectors.

Before arriving at our seats, Josh used some of the money that he hadn’t spent on the ticket on an over-priced and diluted beer. While waiting for Josh to get his beer, I watched the game on TV above the bar and saw a DPR Korea player be given a yellow card within the first minute. Intentions, perhaps, were clear.

The ticket, as a product of culture, sport, politics and money contains much information. The names of 16 multi-national companies are given as the official sponsors – mostly these are Japanese and Korean companies. Japan and Korea had been expected to do well, coincidentally. A silver sticker opposite the information of who is playing (DPR Korea vs Saudi Arabia, btw) with the invocation to UNITE. (Mewonders what the implications of this sticker would be were there to be a match between DPR and South Korea. The rather-delectable possibility didn’t eventuate.)

The patron, crowd member, customer knows exactly where she or he should sit: enter through Gate X, go to Level X, walk around to Aisle X go to Row XX and sit down at Seat XXX. (You are being surveilled, don’t worry. Your security is of the utmost importance to us.) And then on the back of the ticket are 16 points of fine print. Point 6: ‘LOC [Local Organising Committee] reserves the right to make changes to the date, time and/or venue stated on a ticket’. Well, just as well we didn’t go until the last minute, because, hell, the game could have suddenly been moved to John Cain Reserve just to see how well the teams could cope with a little surprise. And another favourite: Point 11: ‘Patrons must comply with all instructions and directions provided by LOC, venue management, police or contracted security personnel at all times.’

I didn’t read these regulations before entering the stadium, but, perhaps the guys behind Josh and me did.

At half-time, when fans were being encouraged to do some kind of stupid dance to win a prize from one of the 16 official sponsors (probably not Makita), some blokes did their bit of larrikinism.

A group of five or so had got dressed up in North Korean military uniforms and brought along masks of the North Korean leader, Kim Jong-il. The crowd at the North End of Melbourne Rectangular Stadium (aka AAMI Park) got out their phones for a little bit of video-action. All in good humour; well, maybe.

The security arrived and told them to remove their masks or that they would be out in a flash. The mock-uniforms and flags were fine; the masks must go. Said-blokes immediately obliged, but, with a few words of minor disgruntlement. The North End crowd booed and were incredulous.

A little later one bloke relayed the story to the person who seemed to be his lady-friend via his mobile phone. A few minutes later, another batch of security arrived to say that there had been reports that the blokes had been using bad language.

DPR Korea had the support of the fans, but from where this support came from is unclear. Saudi Arabia as the bad guys? DPR Korea as underdogs? Neither nation accepts much dissent from within. DPR Korea imploded as the game wore on. Yet at the end of the game they came to the North End and raised their hands and clapped at the fans who had cheered for them.

And then it was over. This was a football game where the crowd could become an audience; having little direct experience of the politics, social conditions, food and life of where the players came from. The crowd-audience came to celebrate the game; enjoy themselves and act as football tourists. The puritanical Wahhabi Islam of Saudi Arabia and the Communism of DPR Korea are irreconcilable ideologies; and football for a moment traversed them. The uniforms and antiquated choreographies of DPR Korea seem like a joke from the outside world – but for North Koreans, the players themselves probably, the conformist rigidity must be more than menacing.

The Asian Cup again was a success being watched by some 12,349 curious fans; but working out how to cheer, who to cheer for or knowing who the players were was probably not the most important matter for fans. Being there was. And thus the ticket as memorabilia.

Andy Fuller writes on football in Indonesia and on footy. He lives in Leiden, The Netherlands. His website is readingsideways.net